Gene sequencing – also known as genetic testing – is the process scientists use to analyze DNA in search of mutations and variations in an effort to discover more about the connection between genes and traits, health and disease. Since the discovery of BRCA 1 in 1994, the sequencing of genes to find mutations has held importance for people with cancer in their family. With advances in biomedical technology, scientists have developed ways to process thousand of genes at the same time (in parallel) and at lower cost than earlier sequencing methods. These next-generation – or “next-gen” – sequencing (NGS) methods have brought opportunities and challenges to the field of genetics. NGS has allowed the development of panel tests that can look for mutations in many genes, including newly identified genes that might increase cancer risk. One of the challenges involves developing regulations to ensure that the resulting information is of maximum benefit to consumers. Recently, the FDA conducted a forum seeking public input about how these tests might be regulated. FORCE attended and testified on this topic.

Benefits and Challenges of NGS: Genetic tests for cancer-causing gene mutations allow people to better understand their risk for cancer, and take appropriate proactive steps against the disease. The test for BRCA mutations was the first commercially available test to help people make informed decisions about cancer prevention. Now, 20 years later, research indicates that knowing one’s BRCA status and taking risk-reducing steps can help people with mutations live longer. Experts use this information to help people make informed health care decisions to manage their cancer risk. But genetics is not an exact science, and even after two decades of research, and there are still health outcomes associated with living with a BRCA mutation that remain unknown.

We know even less about many of the genes included in NGS panel tests. These panel tests are being offered to consumers to help them assess personal cancer risk, but not nearly enough research has been conducted to identify specific risks and outcomes associated with mutations in some genes in these panels, and even less research is available concerning the best ways to manage cancer risk in individuals who have mutations in these genes.

Oversight of Laboratories That Conduct Diagnostic Tests: The federal government has regulatory standards for clinical laboratories to assure the quality of the labs and the tests they perform. But, these government agencies do not regulate other aspects of genetic testing such as:

- Whether the tests have clinical utility

Genetic tests for cancer risk are most useful if results can guide decision-making and most people assume that a test that is commercially available must have value for decision-making. But not all gene changes included in some NGS panel tests have been consistently linked to increased cancer risk. Some gene mutations increase risk, but not enough to change recommendations for risk management. Some genes are not associated with a specific cancer syndrome but still may increase an individual’s risk of some cancers. Currently tests that are run at certified laboratories are not required to meet any standard for clinical usefulness. - How the labs interpret and report variant results

Panel testing returns a high incidence of genes that show a variant of uncertain significance (VUS) – a genetic variation for which the affect on risk of developing cancer is not completely understood. Such results make it exceedingly difficult for experts to advise patients about effective risk-management strategies and to identify family members who should consider genetic testing. Incorrect interpretation of VUS results in BRCA has led to adverse events in some patients, and with the growth of next-gen sequencing, in which VUS rates for some genes may exceed 50%, the incidence of adverse events seems likely to increase. - How the laboratories market these tests to doctors and consumers

People are making medical decisions today based on panel test results, sometimes in the absence of evidence. Therefore, the information that labs provide about these tests, and how they market them to doctors and consumers are significant matters. FORCE was one of the first advocacy organizations to support government oversight of genetic test marketing. In 2009, we provided testimony to the Secretary of Health’s Advisory Committee on this topic, and based on that testimony, the FDA implemented a mechanism for health care providers to report adverse events stemming from laboratory tests.

The full potential of predictive testing can be realized only if patients receive credible and current information that helps them make fully informed decisions. Toward that end, FORCE recently testified that regulatory oversight of genetic testing laboratories ensures that:

- Patients have access to trained genetics experts who are fully independent of testing labs and can provide them with standard-of-care genetic counseling for all the hereditary syndromes for which they may be at risk – both before and after genetic testing.

- Individuals performing genetic counseling and interpreting test results meet minimum certification and continuing education requirements.

- Genetic counselors receive appropriate recognition as health care practitioners by all payers, including Medicare.

- Patients at increased risk for cancer can access services proven to reduce risk and improve survival or health outcomes—including breast MRI and prophylactic oophorectomy.

- Resources are allocated to coordinate policies between the United States Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF), Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), payers, and other agencies.

- The legal provisions of Genetic Information and Non-discrimination Act (GINA) and the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (PPACA) are vigilantly enforced, and expanded protections for life, disability and long-term care insurance are considered.

- A process for reporting adverse events associated with NGS – including misinterpretation of test results – is in place and accessible to patients.

- All laboratories contribute variant data to the publicly accessible database known as ClinVar, and quality control and oversight procedures are created for this public archive that collects information about genomic variation and its relationship to human health.

We will continue to be involved in this dialogue with the regulatory agencies to assure that the best overall health outcomes of consumers remains a priority, and will continue to update you as this topic evolves.

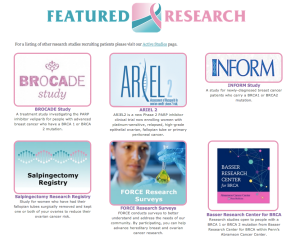

In the meantime FORCE is a resource for all people and families affected by or at increased risk for hereditary breast, ovarian, and related cancers. We are actively building our ABOUT Network Research Registry to study long-term health outcomes for people affected by HBOC and help improve guidelines for medical decision-making.Our registry and our FORCE programs help people who have tested positive for mutations in BRCA, PALB2, PTEN, and other genes linked to cancer, people who have a family history of cancer, those who received inconclusive test results, and those who have not had genetic testing but are concerned about their cancer risk.